Mark Carney’s sovereignty agenda is finally moving, with five nation-building projects announced last week and more to come soon. He also reminded us of his commitment to build a “sovereign digital cloud” — then failed to explain why it matters. Too bad. It does. The government’s plan to plot a new course for Canada will take us into rough seas. The sovereign cloud could be the navigation system that keeps us on course. Here’s why.

The Hybrid Model – Of Vaults and Engines

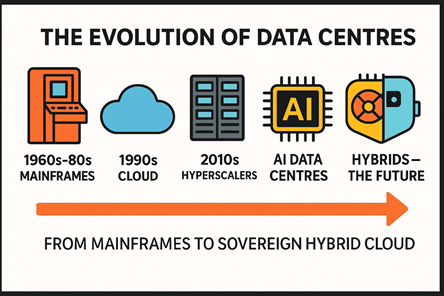

A “sovereign cloud” is built from very specialized data centres. Half a century ago, these were hulking mainframes that consolidated a business’s data in one place—usually the basement of an office tower. By the 1990s, networks were emerging, as data moved online. In the 2000s, warehouse-sized facilities allowed clients to begin renting data services and storage space over the internet. The “cloud” had arrived.

Today, cloud technology has evolved into “hyperscalers”: sprawling complexes with tens of thousands of processors. They dot the American landscape, with new ones coming online every day. Hyperscalers house and manage oceans of internet data — from websites, emails, and social media to hospitals and businesses.

Now a new kind of centre is spreading: AI data centres powered by tens or even hundreds of thousands of specialized chips. An AI data centre is essentially a giant supercomputer, humming with activity. Typically, they have two tasks: train new AI models like ChatGPT and process the requests people send to it.

Hyperscalers and AI data centres thus are very different. Hyperscalers are vaults, storing and managing data; AI centres are engines, transforming it into tools and knowledge. Given Carney’s overarching goal—to support Canadian sovereignty—his version of the cloud must combine both. Canada needs a hybrid.

How the Sovereign Cloud Works

Certainly, the sovereign cloud must be a vault where data can be securely stored and managed. But it must also be a clearing house, ensuring data is accessible and usable for those authorized to see it.

Take health care. Suppose the cloud holds provincial health records along with data from hospitals, community networks, and research facilities. It’s not enough to store this securely — the data must also be available when needed.

Imagine an Ontarian suffering a heart attack in Alberta. The local hospital should be able to see their records. But unless governments have already agreed on who can access what, it won’t happen. If the sovereign cloud is to serve Canadians, it will need agreements like this in many fields, not just health.

On the engine side, the potential is vast. A sovereign cloud loaded with health data could power research, streamline administration, and improve services. Extend this across finance, justice, social services, transportation, the environment, and culture, and the sovereign cloud becomes the Statistics Canada of the AI era: a new kind of policy tool for planning and innovation.

Except, this cloud is more than just a knowledge machine. It has a vast array of practical tools to help administrators and managers put that knowledge to work. Our new AI StatsCan is both a thinker and a doer.

Carney’s plan thus is about much more than building a vault. It’s about creating a new kind of federal-provincial institution for the AI age — one that informs and guides how leaders pursue social, economic, and environmental goals for the future.

But making it work will require negotiation — governments and organizations must agree on how data will be stored, shared, and used. Getting such agreements will take time, and that presents a challenge.

The Window of Opportunity and U.S. Competition

The good news is that the Carney government is making progress on the sovereign cloud. AI Minister Evan Solomon recently announced an MOU with Cohere to look at ways to improve the Public Service. Bell and Telus are both planning major AI centres.

The bad news is that Canada is way behind the Americans. They already have hybrid centres in place, and in the next few years U.S. firms will spend trillions building more—along with a vast menu of plug-and-play services.

These companies will market aggressively to Canadian provinces, municipalities, hospitals, universities, and businesses. Once an organization plugs into a U.S. platform, new services are added continuously, making clients dependent until they are all but locked in. And that’s bad for Canada.

If we want a cloud that truly supports Canadian sovereignty, provinces, hospitals, research organizations, and others need to buy in now — committing their data before U.S. firms capture them. But will they?

Potential partners like Bell, Telus, and Cohere will have quality services to offer. But their ability to compete effectively with American giants will be closely tied to the sovereign cloud’s success. If Canadian governments, organizations, and businesses use the cloud, they will purchase services from its builders. Unfortunately, many of its real benefits will only surface over time, as it matures into a shared Canadian institution and new practices for data-sharing take hold. In the meantime, plug-and-play services from U.S. firms will look very attractive to many Canadian firms, organizations, and even governments.

Ensuring the Canadian cloud succeeds is about more than marketing. Those with data to contribute need to see the long-term value of a pan-Canadian institution. And for that, all of us need to see this as a nation-building project. Yet the way the sovereign cloud has been framed so far doesn’t sound very pan-Canadian. It looks like a federal project, with Ottawa holding the keys. That makes provinces in particular uneasy. Might their data be used in a study that paints them as inefficient or wasteful?

Federal promises of “good faith” won’t cut it. Partners — especially provinces — need real control. Should there be a joint federal-provincial board? Veto rights for provinces? A data trust holding information on behalf of citizens?

Whatever the answers, Carney’s cloud needs a makeover. It should have been cast as a pan-Canadian institution from the start—a pillar of sovereignty in our evolving federal community—rather than a tech project. Canadians, governments, and organizations need to understand what it can achieve and why it matters.

It isn’t too late. But the government needs to draw the right lesson from the tariff morass around us: don’t get bogged down in endless debates. Act. Recast the sovereign cloud as a pan-Canadian data sovereignty engine, a flagship nation-building project—now.

Without this public asset, Canada’s sovereignty vision risks being derailed by U.S. competition. With it, we can lay the foundation for a sovereign digital future — one that secures our data, powers innovation, and strengthens the Canadian project. It should be a top priority for the Carney government, and especially for its AI minister, Evan Solomon.

Don Lenihan PhD is an expert in public engagement with a long-standing focus on how digital technologies are transforming societies, governments, and governance. This column appears weekly. To see earlier instalments in the series, click here.